Psychological Health Regulations: A Focus on Risk Management - a Summary of WorkSafe's Webinar

Almost 14,000 people registered to attend WorkSafe Victoria’s webinar “Psychological Health Regulations: A focus on risk management” held on 27th October 2025.

The webinar was essentially an overview and pointed to a number of resources for employers to access to ensure they are compliant by 1st December 2025.

WorkSafe Representatives explained that employers have always had a duty to provide a safe workplace - including physically and psychologically. However, the new regulations introduce a specific duty relating to the need to identify and control risks associated with psychological health in the workplace.

Psychosocial hazards are factors in the workplace which may create a negative psychological response which can pose a risk to a worker’s health and safety (eg: long hours, work demands, low role clarity, sexual harassment, bullying, etc).

WorkSafe were very clear that The Psychological Health Regulations do not impact any workers eligibility for mental injury claim, as they have no impact on the Workplace Injury Rehabilitation and Compensation (WIRC) Act.

The stated aims of the Regulations were as follows:

1. To strengthen the OHS framework by recognising psychosocial hazards as equally harmful as physical hazards.

2. To provide clearer guidance to employers on their obligations to protect employees from psychological injury.

3. To create specific obligations for Victorian employers to identify and control psychosocial risks in their workplaces.

4. To support employers through a range of tools and non-statutory guidance, including an optional prevention plan template to guide the risk management process.

5. To ensure compliance by providing a practical code to help employers meet their duties under the Regulations.

These regulations are part of a broader effort to address the increasing prevalence of work-related mental injuries and to create a safer, more supportive work environment for all employees.

WorkSafe explained that they was now a prescribed risk management process which requires all employers to identify psychosocial hazards and to control the risks by eliminating or reducing the risks as far as reasonably practicable.

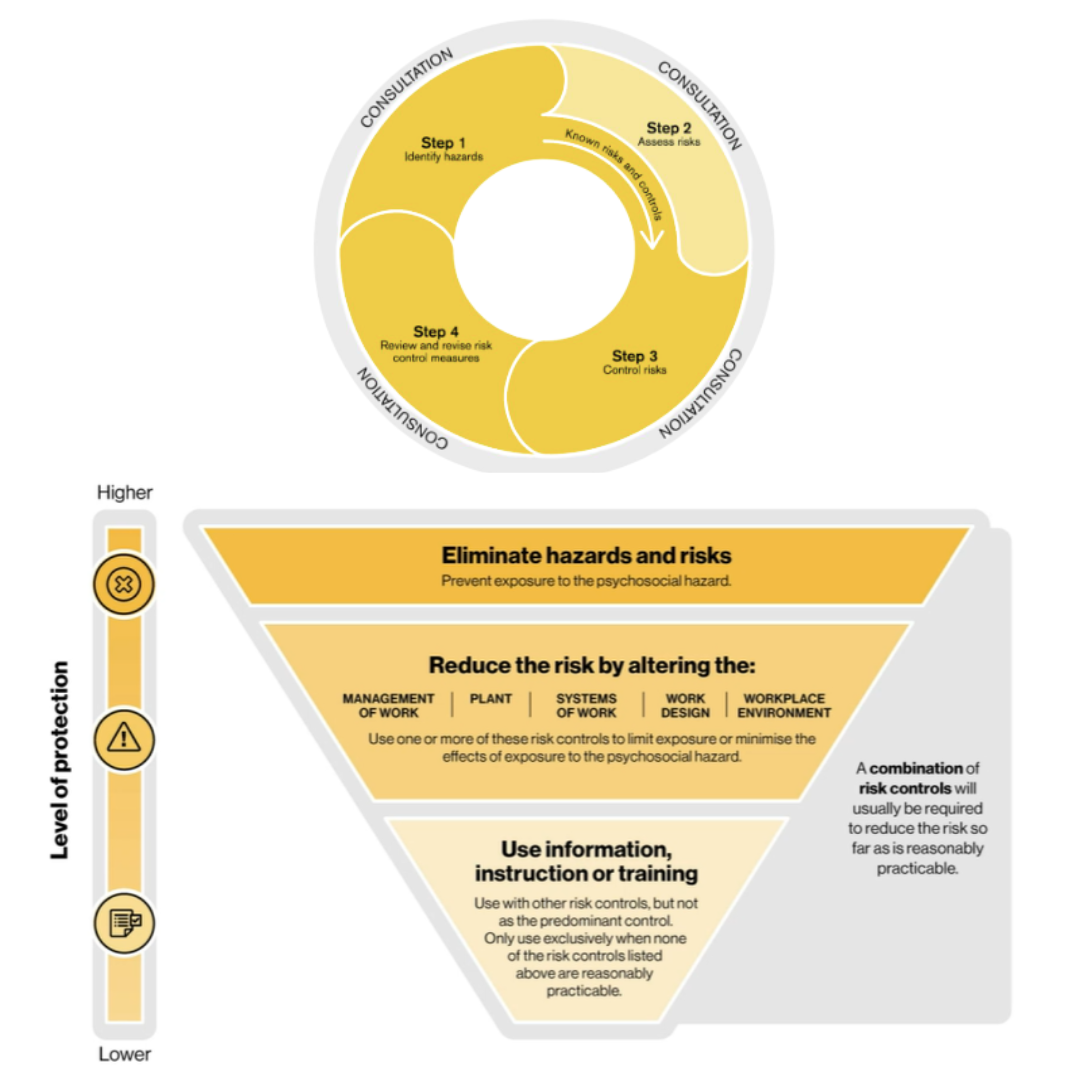

The risk management cycle

(see image below)

Step 1. Identify hazards

Step 2. Assess the risks (including likelihood and consequence)

Step 3: Control the risks (in line with the Hierarchy of Control)

Step 4: Review – monitor, review and revise

Throughout the process, consultation must occur

Hierarchy of Control

(see image below)

The WorkSafe representatives explained the hierarchy of control for psychosocial hazards – noting that elimination is the first priority, and if not possible then there were ways to reduce the risk by making changes to limit exposure or to reduce the effects of exposure to the psychosocial hazard.

In most cases, information, instruction or training will form part of the management of the risk. However, this should be in combination with higher order controls due to the fact that these are the least effective option.

Compliance code

The new compliance code Compliance code: Psychological health | WorkSafe Victoria provides a comprehensive guide to what is required in relation to the new Regulations.

Hazard prevention plan

There is a psychological hazard prevention plan template which can be found at:

Prevention plans for psychosocial hazards | WorkSafe Victoria which is a simple way to go through the risk management process and to document it.

Prevention plans are not mandatory – although strongly encouraged. You can use another method to carry out and record your risk management process.

Enforcement

WorkSafe inspectors may issue improvement notices in the same way as they do for physical hazards. Inspectors will be addressing complaints as well as conducting proactive and strategic workplace visits.

All employers, whether in a large or small business, will be required to comply.

Reporting

Employers need to treat psychological hazards in the same way as physical risks – so you can use your existing internal reporting processes for these too, although they may need to be adapted for this purpose.

There are no new mandatory reporting requirements.

Commencement

The Regulations commence on 1st December 2025, to allow time for employers to prepare.

It was noted by WorkSafe that the obligation to provide a work environment without risks to psychological health is already required under The Act and that there has been significant lead-time to the new Regulations. Therefore, there is an expectation that employers are already across the requirements, however there is still time prior to 1st December 2025 to ensure compliance with The Regulations.

Before December, employers should have in place: evidence of having identified and controlled psychosocial hazards and have a prevention plan (or alternative) in place, noting that consultation with employees must occur as part of this process.

Key takeaways:

- Employees psychological health must be treated equally to physical health.

- The Regulations and Compliance Code provide the guidance to employers on how to do that in the most effective way.

- Employers are encouraged to have a close look at the Compliance Code, which provides practical guidance.

- Risk management is an ongoing process, not a ‘set and forget’, there is a process of continuous improvement. This means ongoing monitoring and review of psychological risks and the controls.

For more information and resources:

WorkSafe psychological health page: Psychological health | WorkSafe Victoria

To view the full webinar: https://tsglive.com.au/HSMweb3